Introduction

The long, arduous struggle to achieve women’s suffrage (the right to vote in political elections) in America was over a century in the making, with suffragists and their allies fighting for the cause through lectures, pilgrimages, rallies, and other actions that brought their case to a largely male-dominated society. At the famed Seneca Falls Convention (1848), pioneering suffragists Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) called in its Declaration of Sentiments for the introduction of women to the political process; it would be another 72 years, however, until the Ninetenth Amendment to the Constitution (1919) allowed women to cast their first votes in the Election of 1920.

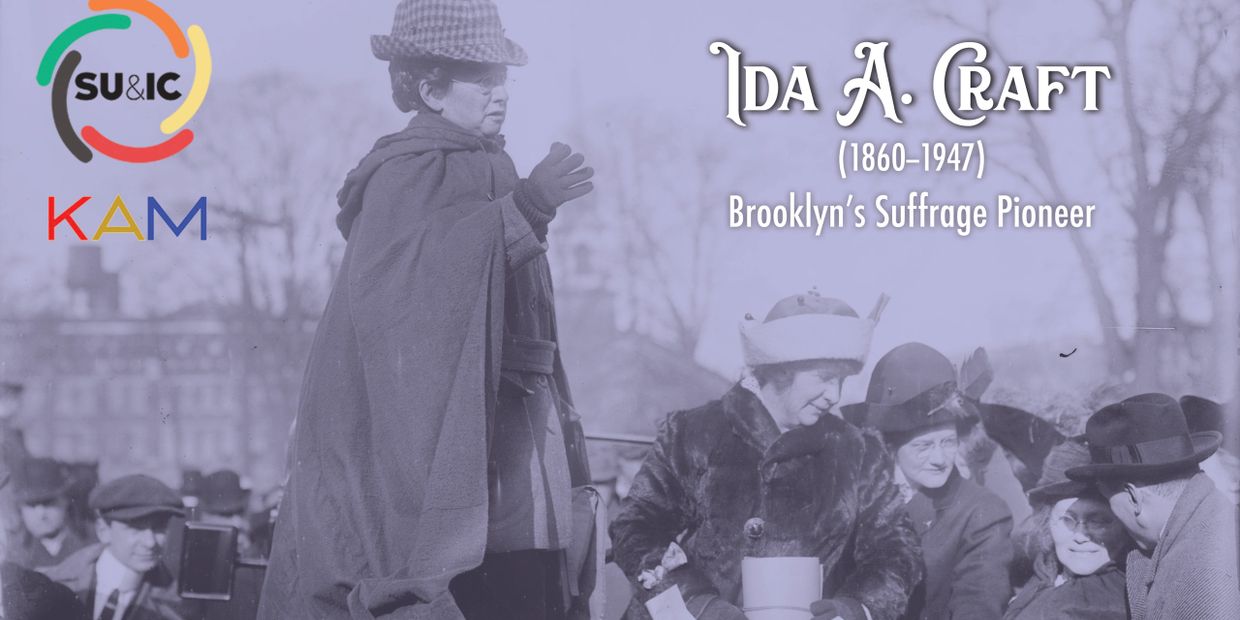

While not as well-known as Mott, Stanton, or Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906), Brooklyn-born Ida Augusta Craft (1860-1947) played a significant role in securing the right to vote for women. The daughter of John Craft (1821-1898) and Eleanor Voorhies Perlee (1824-1913), Ida Craft was born into a relatively well-to-do family: John Craft was a fashionable tailor in Brooklyn Heights; his wife the daughter of a physician. Ida Craft's involvement in politics was extensive, serving as the president of the Kings County Political Equality League and as a member of the Brooklyn’s chapter of the Woman Suffrage Party. The Craft home at 294 Stuyvesant Avenue--which still stands--was the unofficial Brooklyn headquarters of the suffrage movement.

The suffragists, who viewed themeselves as an army of sorts, dubbed her “Colonel” Ida Craft, the second-in-command behind the leader of the suffrage movement in New York, “General” Rosalie Gardiner Jones (1883-1978). With Craft, Jones organized a number of pilgrimage marches from New York to Albany (December 1912) and to Washington, DC (March 1913), hikes that culminated in the presentation of demands to elected officials. The press, somewhat amused by the allusion to suffrage as a military campaign, picked up on the nicknames and frequently referred to both women (as well as other suffragists in their circle) by their adoped nomenclature. An equally vociferous anti-suffrage movement ridiculed these pilgrimage hikes and often jeered the suffragists along the journey, yet they remained undaunted. In May 1913, between the Washington and Boston marches, Eleanor Craft died, leaving her daughter a substantial fortune as well as 294 Stuyvesant Avenue (which Ida Craft would sell a few years later, however).

Throughout Craft remained a faithful Brooklynite. After the grueling nineteen day march, or "tramp" to Albany in December 1912, she claimed a victory for her home borough. "Colonel Craft," noted the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on December 29, "declared with marked emphasis that no little honor goes to Brooklyn, inasmuch as she [Craft] was the first to step off the Renssalaer Bridge on to Albany soil."

Following the grueling marches of 1913 and 1914, Craft remained active in travel, lectures, and organizational duties related to suffrage. She campaigned extensively across Canada and Alaska, as well as the American West pushing for suffrage legislation. On September 30, 1914 the Womens Suffrage Party honored Craft with a mammoth reception celebrating her acheivements. Craft would later serve as a delegate to the International Woman Suffrage Alliance Convention in Rome. By this point, a younger generation had taken up the mantle, most notably Alice Paul (1885-1977), who spearheaded the last, final push for the 19th Amendment. Paul's National Woman's Party--a more progressive splinter group of the older, more conservative National Woman's Suffrage Association--would use more aggressive, and ultimately successful, measures to achieve its goals; while certainly a member of the earlier generation of suffragists, Craft was a stalwart supporter of the new group and its methods.

Unlike Mott, Stanton, and Anthony, Ida A. Craft fortunately lived to see the fruits of her labors, living another 27 years after women secured the right to vote. In 1940 the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported on a reception held on the occasion of her 80th birthday, describing her as "still a spry, sprightly little person...bubbling over with stories of the fight for suffrage and the days when her home on Stuyvesant Ave. was used as suffrage headquarters, for Brooklyn." Ida A. Craft, suffrage pioneer, is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn. The photographs in this digital exhibition, all from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, document the suffragist pilgrimages as well as the role Ida A. Craft played in this pivotal moment in American history.